Understanding Lambda function scaling

Concurrency is the number of in-flight requests that your Amazon Lambda function is

handling at the same time. For each concurrent request, Lambda provisions a separate instance of your execution

environment. As your functions receive more requests, Lambda automatically handles scaling the number of execution

environments until you reach your account's concurrency limit. By default, Lambda provides your account with a total

concurrency limit of 1,000 concurrent executions across all functions in an Amazon Web Services Region. To support your specific

account needs, you can request a quota

increase

This topic explains concurrency concepts and function scaling in Lambda. By the end of this topic, you'll be able to understand how to calculate concurrency, visualize the two main concurrency control options (reserved and provisioned), estimate appropriate concurrency control settings, and view metrics for further optimization.

Understanding and visualizing concurrency

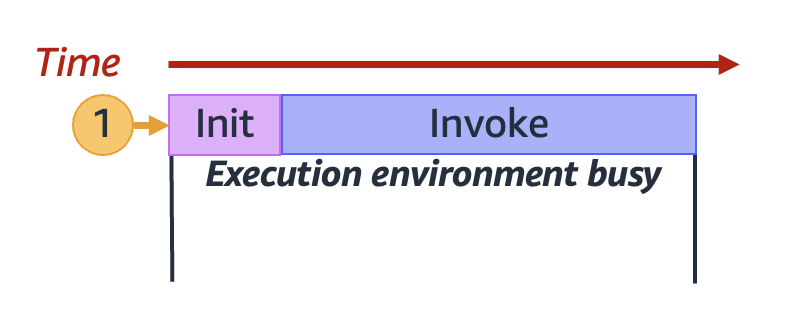

Lambda invokes your function in a secure and isolated execution environment. To handle a request, Lambda must first initialize an execution environment (the Init phase), before using it to invoke your function (the Invoke phase):

Note

Actual Init and Invoke durations can vary depending on many factors, such as the runtime you choose and the Lambda function code. The previous diagram isn't meant to represent the exact proportions of Init and Invoke phase durations.

The previous diagram uses a rectangle to represent a single execution environment. When your function

receives its very first request (represented by the yellow circle with label 1), Lambda creates

a new execution environment and runs the code outside your main handler during the Init phase. Then, Lambda

runs your function's main handler code during the Invoke phase. During this entire process, this execution

environment is busy and cannot process other requests.

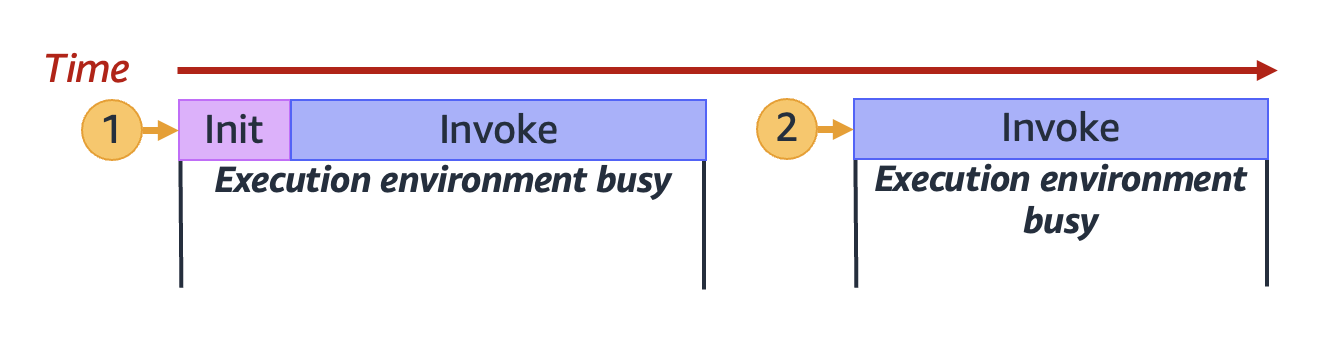

When Lambda finishes processing the first request, this execution environment can then process additional requests for the same function. For subsequent requests, Lambda doesn't need to re-initialize the environment.

In the previous diagram, Lambda reuses the execution environment to handle the second request

(represented by the yellow circle with label 2).

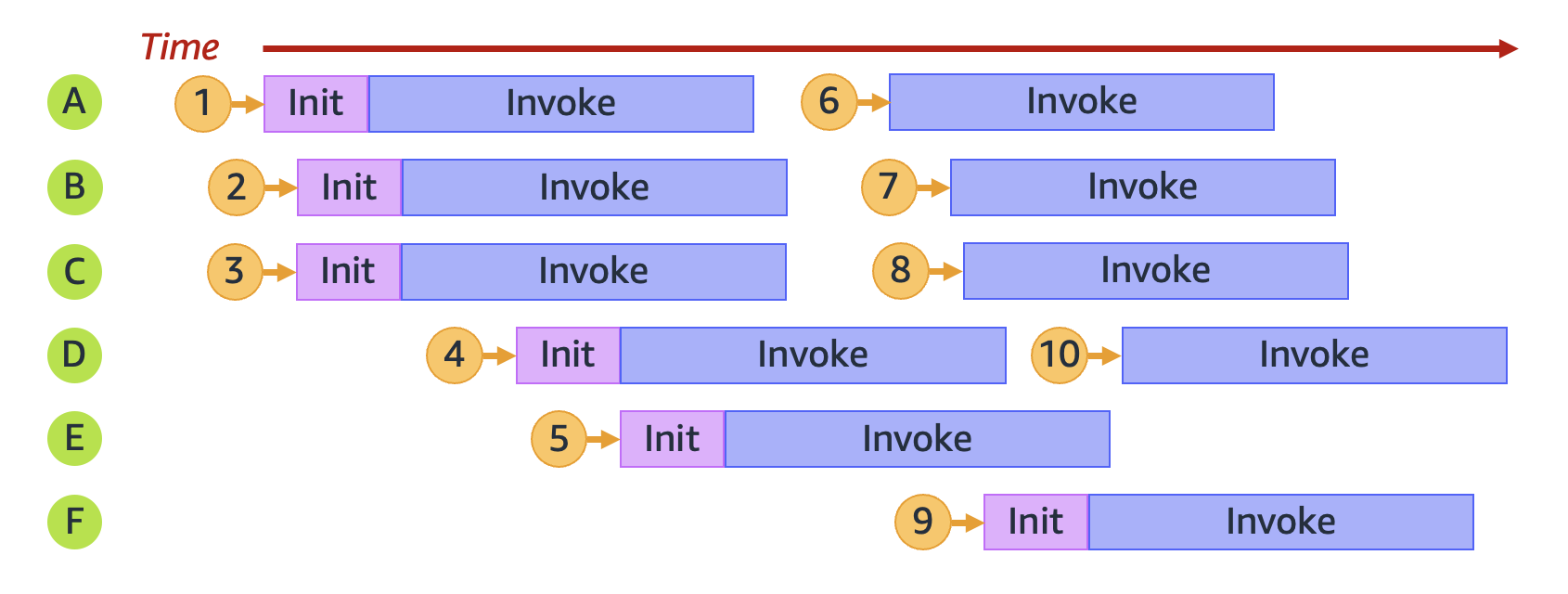

So far, we've focused on just a single instance of your execution environment (that is, a concurrency of 1). In practice, Lambda may need to provision multiple execution environment instances in parallel to handle all incoming requests. When your function receives a new request, one of two things can happen:

-

If a pre-initialized execution environment instance is available, Lambda uses it to process the request.

-

Otherwise, Lambda creates a new execution environment instance to process the request.

For example, let's explore what happens when your function receives 10 requests:

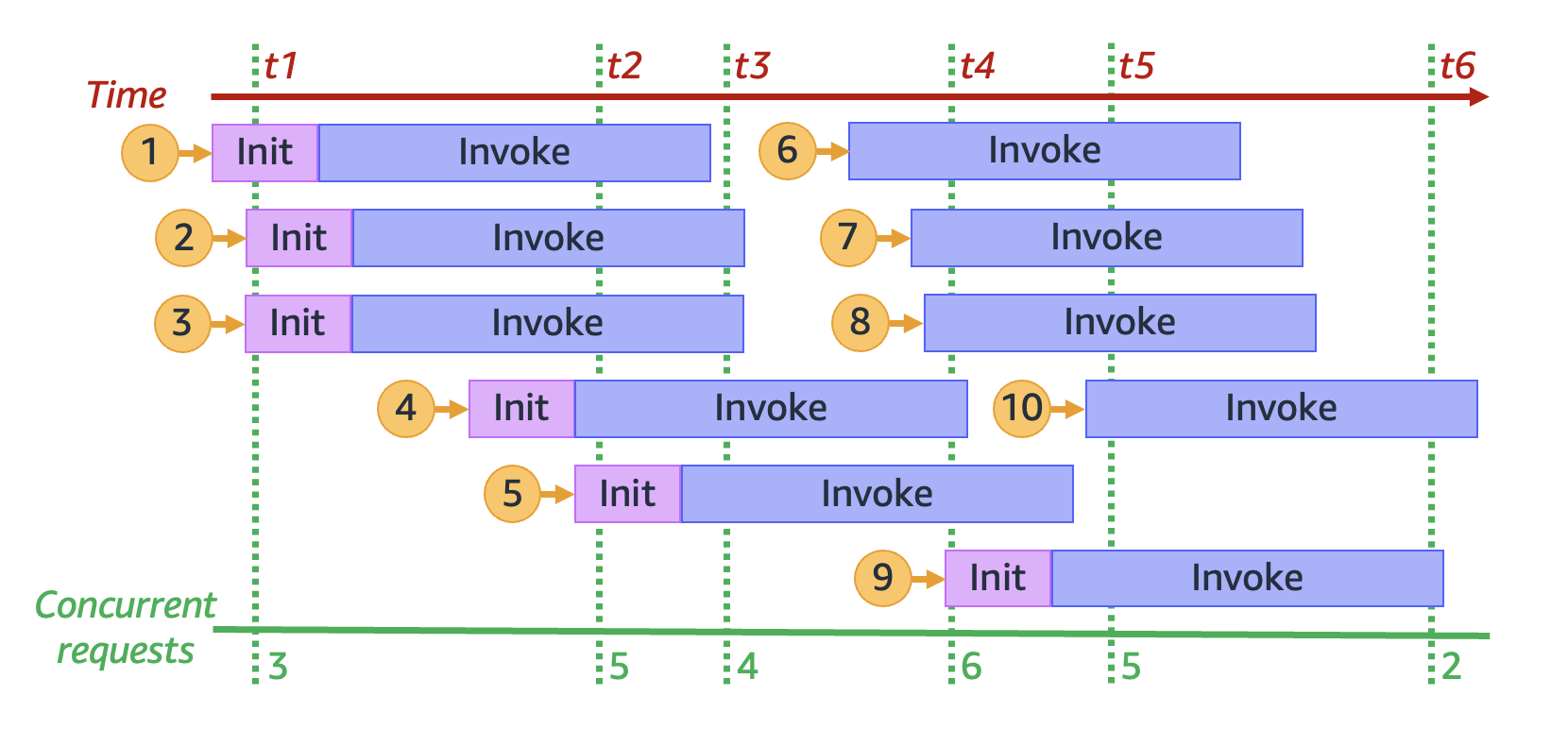

In the previous diagram, each horizontal plane represents a single execution environment instance (labeled

from A through F). Here's how Lambda handles each request:

| Request | Lambda behavior | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Provisions new environment A |

This is the first request; no execution environment instances are available. |

|

2 |

Provisions new environment B |

Existing execution environment instance A is busy. |

|

3 |

Provisions new environment C |

Existing execution environment instances A and B are both busy. |

|

4 |

Provisions new environment D |

Existing execution environment instances A, B, and C are all busy. |

|

5 |

Provisions new environment E |

Existing execution environment instances A, B, C, and D are all busy. |

|

6 |

Reuses environment A |

Execution environment instance A has finished processing request 1 and is now available. |

|

7 |

Reuses environment B |

Execution environment instance B has finished processing request 2 and is now available. |

|

8 |

Reuses environment C |

Execution environment instance C has finished processing request 3 and is now available. |

|

9 |

Provisions new environment F |

Existing execution environment instances A, B, C, D, and E are all busy. |

|

10 |

Reuses environment D |

Execution environment instance D has finished processing request 4 and is now available. |

As your function receives more concurrent requests, Lambda scales up the number of execution environment instances in response. The following animation tracks the number of concurrent requests over time:

By freezing the previous animation at six distinct points in time, we get the following diagram:

In the previous diagram, we can draw a vertical line at any point in time and count the number of environments

that intersect this line. This gives us the number of concurrent requests at that point in time. For example, at

time t1, there are three active environments serving three concurrent requests. The maximum number of

concurrent requests in this simulation occurs at time t4, when there are six active environments

serving six concurrent requests.

To summarize, your function's concurrency is the number of concurrent requests that it's handling at the same time. In response to an increase in your function's concurrency, Lambda provisions more execution environment instances to meet request demand.

Calculating concurrency for a function

In general, concurrency of a system is the ability to process more than one task simultaneously. In Lambda, concurrency is the number of in-flight requests that your function is handling at the same time. A quick and practical way of measuring concurrency of a Lambda function is to use the following formula:

Concurrency = (average requests per second) * (average request duration in seconds)

Concurrency differs from requests per second. For example, suppose your function receives 100 requests per second on average. If the average request duration is one second, then it's true that the concurrency is also 100:

Concurrency = (100 requests/second) * (1 second/request) = 100

However, if the average request duration is 500 ms, then the concurrency is 50:

Concurrency = (100 requests/second) * (0.5 second/request) = 50

What does a concurrency of 50 mean in practice? If the average request duration is 500 ms, then you can think of an instance of your function as being able to handle two requests per second. Then, it takes 50 instances of your function to handle a load of 100 requests per second. A concurrency of 50 means that Lambda must provision 50 execution environment instances to efficiently handle this workload without any throttling. Here's how to express this in equation form:

Concurrency = (100 requests/second) / (2 requests/second) = 50

If your function receives double the number of requests (200 requests per second), but only requires half the time to process each request (250 ms), then the concurrency is still 50:

Concurrency = (200 requests/second) * (0.25 second/request) = 50

Suppose you have a function that takes, on average, 200 ms to run. During peak load, you observe 5,000 requests per second. What is the concurrency of your function during peak load?

The average function duration is 200 ms, or 0.2 seconds. Using the concurrency formula, you can plug in the numbers to get a concurrency of 1,000:

Concurrency = (5,000 requests/second) * (0.2 seconds/request) = 1,000

Alternatively, an average function duration of 200 ms means that your function can process 5 requests per second. To handle the 5,000 request per second workload, you need 1,000 execution environment instances. Thus, the concurrency is 1,000:

Concurrency = (5,000 requests/second) / (5 requests/second) = 1,000

Understanding reserved concurrency and provisioned concurrency

By default, your account has a concurrency limit of 1,000 concurrent executions across all functions in a Region. Your functions share this pool of 1,000 concurrency on an on-demand basis. Your functions experiences throttling (that is, they start to drop requests) if you run out of available concurrency.

Some of your functions might be more critical than others. As a result, you might want to configure concurrency settings to ensure that critical functions get the concurrency that they need. There are two types of concurrency controls available: reserved concurrency and provisioned concurrency.

-

Use reserved concurrency to set both the maximum and minimum number of concurrent instances to reserve a portion of your account's concurrency for a function. This is useful if you don't want other functions taking up all the available unreserved concurrency. When a function has reserved concurrency, no other function can use that concurrency.

-

Use provisioned concurrency to pre-initialize a number of environment instances for a function. This is useful for reducing cold start latencies.

Reserved concurrency

If you want to guarantee that a certain amount of concurrency is available for your function at any time, use reserved concurrency.

Reserved concurrency sets the maximum and minimum number of concurrent instances that you want to allocate to your function. When you dedicate reserved concurrency to a function, no other function can use that concurrency. In other words, setting reserved concurrency can impact the concurrency pool that's available to other functions. Functions that don't have reserved concurrency share the remaining pool of unreserved concurrency.

Configuring reserved concurrency counts towards your overall account concurrency limit. There is no charge for configuring reserved concurrency for a function.

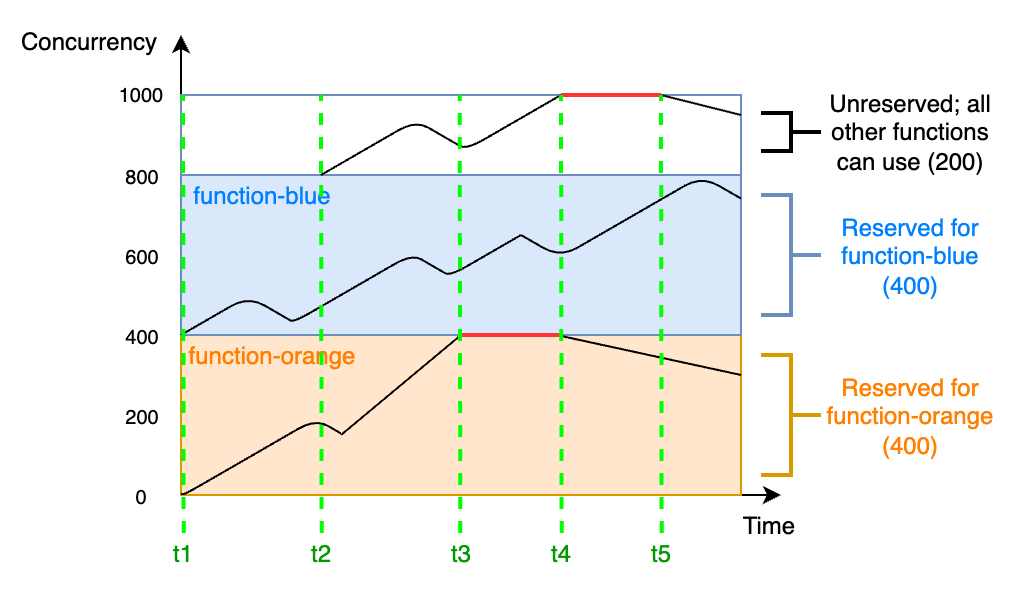

To better understand reserved concurrency, consider the following diagram:

In this diagram, your account concurrency limit for all the functions in this Region is at the default limit

of 1,000. Suppose you have two critical functions, function-blue and function-orange,

that routinely expect to get high invocation volumes. You decide to give 400 units of reserved concurrency to

function-blue, and 400 units of reserved concurrency to function-orange. In this

example, all other functions in your account must share the remaining 200 units of unreserved

concurrency.

The diagram has five points of interest:

-

At

t1, bothfunction-orangeandfunction-bluebegin receiving requests. Each function begins to use up its allocated portion of reserved concurrency units. -

At

t2,function-orangeandfunction-bluesteadily receive more requests. At the same time, you deploy some other Lambda functions, which begin receiving requests. You don't allocate reserved concurrency to these other functions. They begin using the remaining 200 units of unreserved concurrency. -

At

t3,function-orangehits the max concurrency of 400. Although there is unused concurrency elsewhere in your account,function-orangecannot access it. The red line indicates thatfunction-orangeis experiencing throttling, and Lambda may drop requests. -

At

t4,function-orangestarts to receive fewer requests and is no longer throttling. However, your other functions experience a spike in traffic and begin throttling. Although there is unused concurrency elsewhere in your account, these other functions cannot access it. The red line indicates that your other functions are experiencing throttling. -

At

t5, other functions start to receive fewer requests and are no longer throttling.

From this example, notice that reserving concurrency has the following effects:

-

Your function can scale independently of other functions in your account. All of your account's functions in the same Region that don't have reserved concurrency share the pool of unreserved concurrency. Without reserved concurrency, other functions can potentially use up all of your available concurrency. This prevents critical functions from scaling up if needed.

-

Your function can't scale out of control. Reserved concurrency caps your function's maximum and minimum concurrency. This means that your function can't use concurrency reserved for other functions, or concurrency from the unreserved pool. Additionally, reserved concurrency acts as both a lower and upper bound - it reserves the specified capacity exclusively for your function while also preventing it from scaling beyond that limit. You can reserve concurrency to prevent your function from using all the available concurrency in your account, or from overloading downstream resources.

-

You may not be able to use all of your account's available concurrency. Reserving concurrency counts towards your account concurrency limit, but this also means that other functions cannot use that chunk of reserved concurrency. If your function doesn't use up all of the concurrency that you reserve for it, you're effectively wasting that concurrency. This isn't an issue unless other functions in your account could benefit from the wasted concurrency.

To learn how to manage reserved concurrency settings for your functions, see Configuring reserved concurrency for a function.

Provisioned concurrency

You use reserved concurrency to define the maximum number of execution environments reserved for a Lambda function. However, none of these environments come pre-initialized. As a result, your function invocations may take longer because Lambda must first initialize the new environment before being able to use it to invoke your function. When Lambda has to initialize a new environment in order to carry out an invocation, this is known as a cold start. To mitigate cold starts, you can use provisioned concurrency.

Provisioned concurrency is the number of pre-initialized execution environments that you want to allocate to your function. If you set provisioned concurrency on a function, Lambda initializes that number of execution environments so that they are prepared to respond immediately to function requests.

Note

Using provisioned concurrency incurs additional charges to your account. If you're working with the Java 11 or Java 17 runtimes, you can also use Lambda SnapStart to mitigate cold start issues at no additional cost. SnapStart uses cached snapshots of your execution environment to significantly improve startup performance. You cannot use both SnapStart and provisioned concurrency on the same function version. For more information about SnapStart features, limitations, and supported Regions, see Improving startup performance with Lambda SnapStart.

When using provisioned concurrency, Lambda still recycles execution environments in the background. For example, this can occur after an invocation failure. However, at any given time, Lambda always ensures that the number of pre-initialized environments is equal to the value of your function's provisioned concurrency setting. Importantly, even if you're using provisioned concurrency, you can still experience a cold start delay if Lambda has to reset the execution environment.

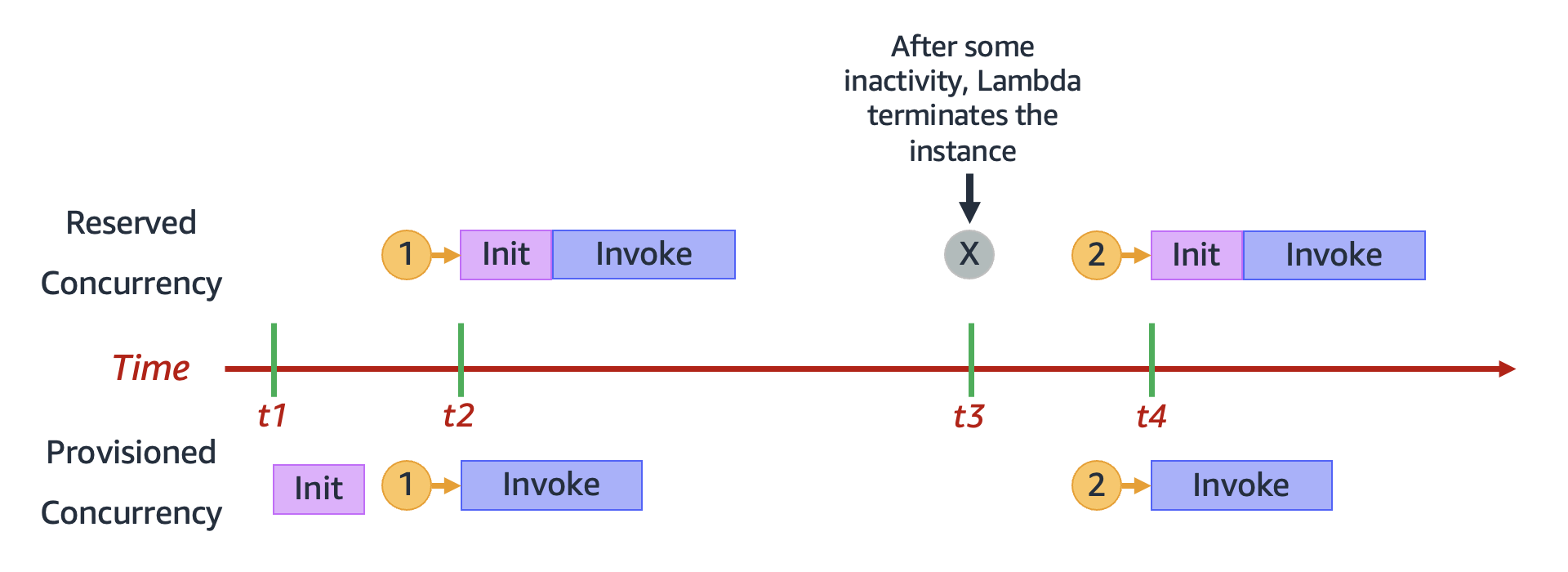

In contrast, when using reserved concurrency, Lambda may completely terminate an environment after a period of inactivity. The following diagram illustrates this by comparing the lifecycle of a single execution environment when you configure your function using reserved concurrency compared to provisioned concurrency.

The diagram has four points of interest:

| Time | Reserved concurrency | Provisioned concurrency |

|---|---|---|

|

t1 |

Nothing happens. |

Lambda pre-initializes an execution environment instance. |

|

t2 |

Request 1 comes in. Lambda must initialize a new execution environment instance. |

Request 1 comes in. Lambda uses the pre-initialized environment instance. |

|

t3 |

After some inactivity, Lambda terminates the active environment instance. |

Nothing happens. |

|

t4 |

Request 2 comes in. Lambda must initialize a new execution environment instance. |

Request 2 comes in. Lambda uses the pre-initialized environment instance. |

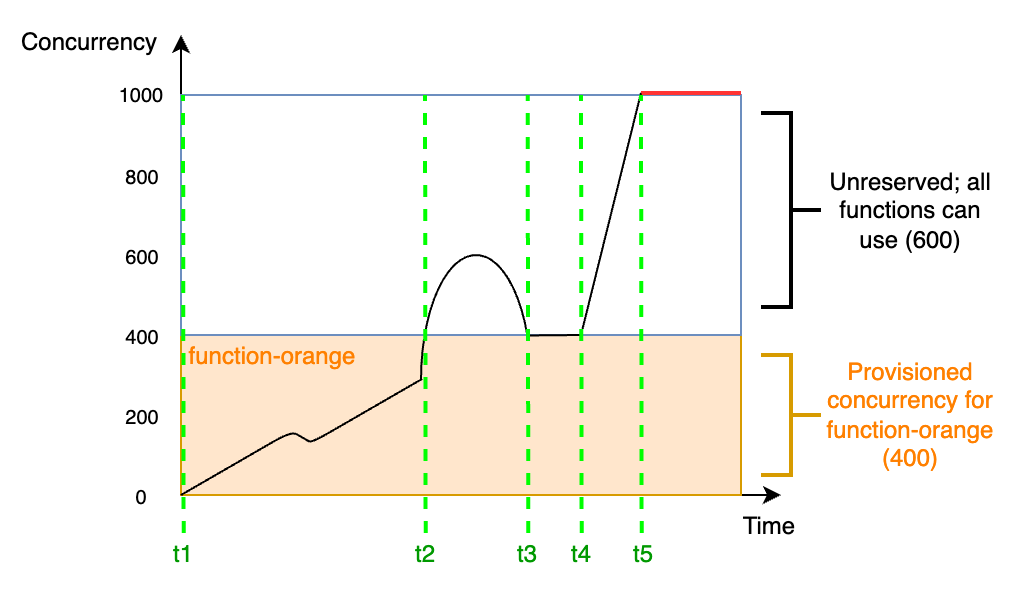

To better understand provisioned concurrency, consider the following diagram:

In this diagram, you have an account concurrency limit of 1,000. You decide to give 400 units of provisioned

concurrency to function-orange. All functions in your account, including

function-orange, can use the remaining 600 units of unreserved concurrency.

The diagram has five points of interest:

-

At

t1,function-orangebegins receiving requests. Since Lambda has pre-initialized 400 execution environment instances,function-orangeis ready for immediate invocation. -

At

t2,function-orangereaches 400 concurrent requests. As a result,function-orangeruns out of provisioned concurrency. However, since there's still unreserved concurrency available, Lambda can use this to handle additional requests tofunction-orange(there's no throttling). Lambda must create new instances to serve these requests, and your function may experience cold start latencies. -

At

t3,function-orangereturns to 400 concurrent requests after a brief spike in traffic. Lambda is again able to handle all requests without cold start latencies. -

At

t4, functions in your account experience a burst in traffic. This burst can come fromfunction-orangeor any other function in your account. Lambda uses unreserved concurrency to handle these requests. -

At

t5, functions in your account reach the maximum concurrency limit of 1,000, and experience throttling.

The previous example considered only provisioned concurrency. In practice, you can set both provisioned concurrency and reserved concurrency on a function. You might do this if you had a function that handles a consistent load of invocations on weekdays, but routinely sees spikes of traffic on weekends. In this case, you could use provisioned concurrency to set a baseline amount of environments to handle request during weekdays, and use reserved concurrency to handle the weekend spikes. Consider the following diagram:

In this diagram, suppose that you configure 200 units of provisioned concurrency and 400 units of

reserved concurrency for function-orange. Because you configured reserved concurrency,

function-orange cannot use any of the 600 units of unreserved concurrency.

This diagram has five points of interest:

-

At

t1,function-orangebegins receiving requests. Since Lambda has pre-initialized 200 execution environment instances,function-orangeis ready for immediate invocation. -

At

t2,function-orangeuses up all its provisioned concurrency.function-orangecan continue serving requests using reserved concurrency, but these requests may experience cold start latencies. -

At

t3,function-orangereaches 400 concurrent requests. As a result,function-orangeuses up all its reserved concurrency. Sincefunction-orangecannot use unreserved concurrency, requests begin to throttle. -

At

t4,function-orangestarts to receive fewer requests, and no longer throttles. -

At

t5,function-orangedrops down to 200 concurrent requests, so all requests are again able to use provisioned concurrency (that is, no cold start latencies).

Both reserved concurrency and provisioned concurrency count towards your account concurrency limit and Regional quotas. In other words, allocating reserved and provisioned concurrency can impact the concurrency pool that's available to other functions. Configuring provisioned concurrency incurs charges to your Amazon Web Services account.

Note

If the amount of provisioned concurrency on a function's versions and aliases adds up to the function's reserved

concurrency, then all invocations run on provisioned concurrency. This configuration also has the effect of

throttling the unpublished version of the function ($LATEST), which prevents it from executing.

You can't allocate more provisioned concurrency than reserved concurrency for a function.

To manage provisioned concurrency settings for your functions, see Configuring provisioned concurrency for a function. To automate provisioned concurrency scaling based on a schedule or application utilization, see Using Application Auto Scaling to automate provisioned concurrency management.

How Lambda allocates provisioned concurrency

Provisioned concurrency doesn't come online immediately after you configure it. Lambda starts allocating provisioned concurrency after a minute or two of preparation. For each function, Lambda can provision up to 6,000 execution environments every minute, regardless of Amazon Web Services Region. This is exactly the same as the concurrency scaling rate for functions.

When you submit a request to allocate provisioned concurrency, you can't access any of those environments until Lambda completely finishes allocating them. For example, if you request 5,000 provisioned concurrency, none of your requests can use provisioned concurrency until Lambda completely finishes allocating the 5,000 execution environments.

Comparing reserved concurrency and provisioned concurrency

The following table summarizes and compares reserved and provisioned concurrency.

| Topic | Reserved concurrency | Provisioned concurrency |

|---|---|---|

|

Definition |

Maximum number of execution environment instances for your function. |

Set number of pre-provisioned execution environment instances for your function. |

|

Provisioning behavior |

Lambda provisions new instances on an on-demand basis. |

Lambda pre-provisions instances (that is, before your function starts receiving requests). |

|

Cold start behavior |

Cold start latency possible, since Lambda must create new instances on-demand. |

Cold start latency not possible, since Lambda doesn't have to create instances on-demand. |

|

Throttling behavior |

Function throttled when reserved concurrency limit reached. |

If reserved concurrency not set: function uses unreserved concurrency when provisioned concurrency limit reached. If reserved concurrency set: function throttled when reserved concurrency limit reached. |

|

Default behavior if not set |

Function uses unreserved concurrency available in your account. |

Lambda doesn't pre-provision any instances. Instead, if reserved concurrency not set: function uses unreserved concurrency available in your account. If reserved concurrency set: function uses reserved concurrency. |

|

Pricing |

No additional charge. |

Incurs additional charges. |

Understanding concurrency and requests per second

As mentioned in the previous section, concurrency differs from requests per second. This is an especially important distinction to make when working with functions that have an average request duration of less than 100 ms.

Across all functions in your account, Lambda enforces a requests per second limit that's equal to 10 times your account concurrency. For example, since the default account concurrency limit is 1,000, functions in your account can handle a maximum of 10,000 requests per second.

For example, consider a function with an average request duration of 50 ms. At 20,000 requests per second, here's the concurrency of this function:

Concurrency = (20,000 requests/second) * (0.05 second/request) = 1,000

Based on this result, you might expect that the account concurrency limit of 1,000 is sufficient to handle this load. However, because of the 10,000 requests per second limit, your function can only handle 10,000 requests per second out of the 20,000 total requests. This function experiences throttling.

The lesson is that you must consider both concurrency and requests per second when configuring concurrency settings for your functions. In this case, you need to request an account concurrency limit increase to 2,000, since this would increase your total requests per second limit to 20,000.

Note

Based on this request per second limit, it's incorrect to say that each Lambda execution environment can handle only a maximum of 10 requests per second. Instead of observing the load on any individual execution environment, Lambda only considers overall concurrency and overall requests per second when calculating your quotas.

Suppose that you have a function that takes, on average, 20 ms to run. During peak load, you observe 30,000 requests per second. What is the concurrency of your function during peak load?

The average function duration is 20 ms, or 0.02 seconds. Using the concurrency formula, you can plug in the numbers to get a concurrency of 600:

Concurrency = (30,000 requests/second) * (0.02 seconds/request) = 600

By default, the account concurrency limit of 1,000 seems sufficient to handle this load. However, the requests per second limit of 10,000 isn't enough to handle the incoming 30,000 requests per second. To fully accommodate the 30,000 requests, you need to request an account concurrency limit increase to 3,000 or higher.

The requests per second limit applies to all quotas in Lambda that involve concurrency. In other words, it applies to synchronous on-demand functions, functions that use provisioned concurrency, and concurrency scaling behavior. For example, here are a few scenarios where you must carefully consider both your concurrency and request per second limits:

-

A function using on-demand concurrency can experience a burst increase of 500 concurrency every 10 seconds, or by 5,000 requests per second every 10 seconds, whichever happens first.

-

Suppose you have a function that has a provisioned concurrency allocation of 10. This function spills over into on-demand concurrency after 10 concurrency or 100 requests per second, whichever happens first.

Concurrency quotas

Lambda sets quotas for the total amount of concurrency that you can use across all functions in a Region. These quotas exist on two levels:

-

At the account level, your functions can have up to 1,000 units of concurrency by default. To increase this limit, see Requesting a quota increase in the Service Quotas User Guide.

-

At the function level, you can reserve up to 900 units of concurrency across all your functions by default. Regardless of your total account concurrency limit, Lambda always reserves 100 units of concurrency for your functions that don't explicitly reserve concurrency. For example, if you increased your account concurrency limit to 2,000, then you can reserve up to 1,900 units of concurrency at the function level.

-

At both the account level and the function level, Lambda also enforces a requests per second limit of equal to 10 times the corresponding concurrency quota. For instance, this applies to account-level concurrency, functions using on-demand concurrency, functions using provisoned concurrency, and concurrency scaling behavior. For more information, see Understanding concurrency and requests per second.

To check your current account level concurrency quota, use the Amazon Command Line Interface (Amazon CLI) to run the following command:

aws lambda get-account-settings

You should see output that looks like the following:

{ "AccountLimit": { "TotalCodeSize": 80530636800, "CodeSizeUnzipped": 262144000, "CodeSizeZipped": 52428800, "ConcurrentExecutions": 1000, "UnreservedConcurrentExecutions": 900 }, "AccountUsage": { "TotalCodeSize": 410759889, "FunctionCount": 8 } }

ConcurrentExecutions is your total account-level concurrency quota.

UnreservedConcurrentExecutions is the amount of reserved concurrency that you can still allocate to

your functions.

As your function receives more requests, Lambda automatically scales up the number of execution environments to handle these requests until your account reaches its concurrency quota. However, to protect against over-scaling in response to sudden bursts of traffic, Lambda limits how fast your functions can scale. This concurrency scaling rate is the maximum rate at which functions in your account can scale in response to increased requests. (That is, how quickly Lambda can create new execution environments.) The concurrency scaling rate differs from the account-level concurrency limit, which is the total amount of concurrency available to your functions.

In each Amazon Web Services Region, and for each function, your concurrency scaling rate is 1,000 execution environment instances every 10 seconds (or 10,000 requests per second every 10 seconds). In other words, every 10 seconds, Lambda can allocate at most 1,000 additional execution environment instances, or accommodate 10,000 additional requests per second, to each of your functions.

Usually, you don't need to worry about this limitation. Lambda's scaling rate is sufficient for most use cases.

Importantly, the concurrency scaling rate is a function-level limit. This means that each function in your account can scale independently of other functions.

For more information about scaling behavior, see Lambda scaling behavior.